Concentric

November 30, 2023 – January 20, 2024

Satchel Projects is pleased to present Concentric, a group exhibition on view from November 30, 2023 through January 20, 2024. An opening reception will be held on Thursday, Nov 30 between 6–8 PM.

Concentric features nine artists whose work addresses notions of place as it shapes identity. Starting from the center — the intimate and personal space of home — the exhibition then extends outward to include geographic, social, and geopolitical constructs of place. The show includes works by An Pham, Elizabeth Flood, Carol Chediak, Mike Cloud, Yamini Nayar, Marie Watt, Duane Slick, Amy Yoshitsu, and Zarina, with accompanying text by Sarah Walko.

Author Wendell Berry wrote, “We walked always in beauty, it seemed to me…We did not often speak. The place spoke for us and was a kind of speech. We spoke to each other in the things we saw.” Concentric focuses on the relationship between person and place, the ways we are connected to and shaped by the environments and terrains we inhabit physically, emotionally, and socially. These inquiries probe into the complexities of meaningful place, which can be tied to warmth, belonging and memory, but can also be troubled and contested. The works in Concentric speak to the intricate interconnections inherent in the notions of place we carry with us as we move through the world.

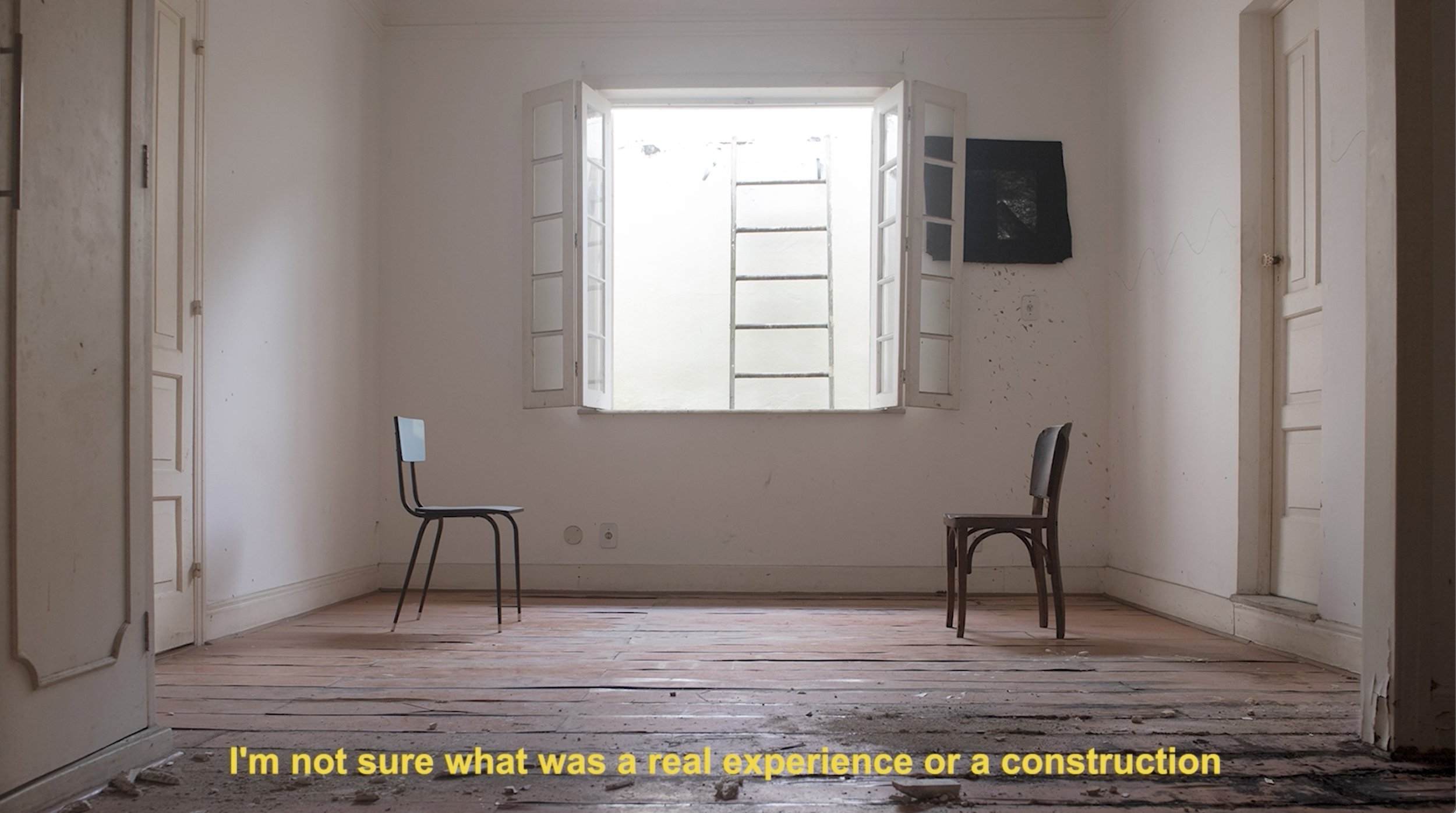

Carol Chediak’s relational audio/visual performance piece, Quarto de Infância (Childhood Bedroom), brings to mind Vladimir Nabokov’s memoir Speak, Memory. In it he writes “I see again my schoolroom in Vyra, the blue roses of the wallpaper, the open window… . Everything is as it should be, nothing will ever change, nobody will ever die.” Chediak’s piece takes place in the ruin of her childhood bedroom in Rio de Janeiro, where members of the local community were invited to visit and describe their own childhood bedrooms. The resulting work evokes absence and loss as well as connection and empathy. It suggests there are always places in the world in which we truly never fully leave.

Duane Slick’s Coyote series is part of his ongoing investigation into early tribal creation stories, where the coyote plays the role of trickster and clown, a benevolent beholder. The coyote is a seminal figure in indigenous culture, and in Slick’s work it stands as a symbol of perseverance and creativity in its ability to live off the land. Slick’s painting Silver Sky explores the spiritual through the physical, integrating secular Modernist abstraction with the beliefs and traditions of his Native American ancestry. His paintings combine the landscape of his upbringing in Iowa and the symbology and beliefs of his heritage as a citizen of both the Meskwaki (Fox of Iowa) and Ho-Chunk (Nebraska) Nations. The work grapples with the role of the sacred and the secular in the context of society in his communities of origin. They are steeped in coded imagery and create layers that unfold gradually.

Elizabeth Flood paints historically significant landscapes from direct observation. She is often exposed to the elements and physically punishing conditions in pursuit of a deeper understanding of her given subject matter. Battlefield (Chancellorsville, Summer) depicts the land where extreme violence took place and asks the viewer to pause, to visually traverse, to not look away – to feel what the land feels. Flood’s paintings re-embody the landscape with a sense of excavation, an uncovering of history and how the political climate affects topography, which in turn reveals its narrative.

Marie Watt’s piece Chords to Other Chords (Home) is a prototype for a future public installation. Watt’s states, “By anchoring the neon phrase TURTLE ISLAND in multiple spaces over time and simultaneously, the work is both a call and response; calling back to past ancestors and calling forward to future generations.” This site-specific piece presents the original name for North America. As Watt explains, “this phrase, a term of endearment, story and title, is ancient and modern, sovereign and instructional. The act of amplifying TURTLE ISLAND is an act of resistance.” The graphic text form is a powerful reclamation of a name, highlighting the power of language, which can both carry something forward and breathe life back into it. Watt’s words-as-resistance recall poet Joy Harjo, who states “I took up a pen and it became a way to make a road.”

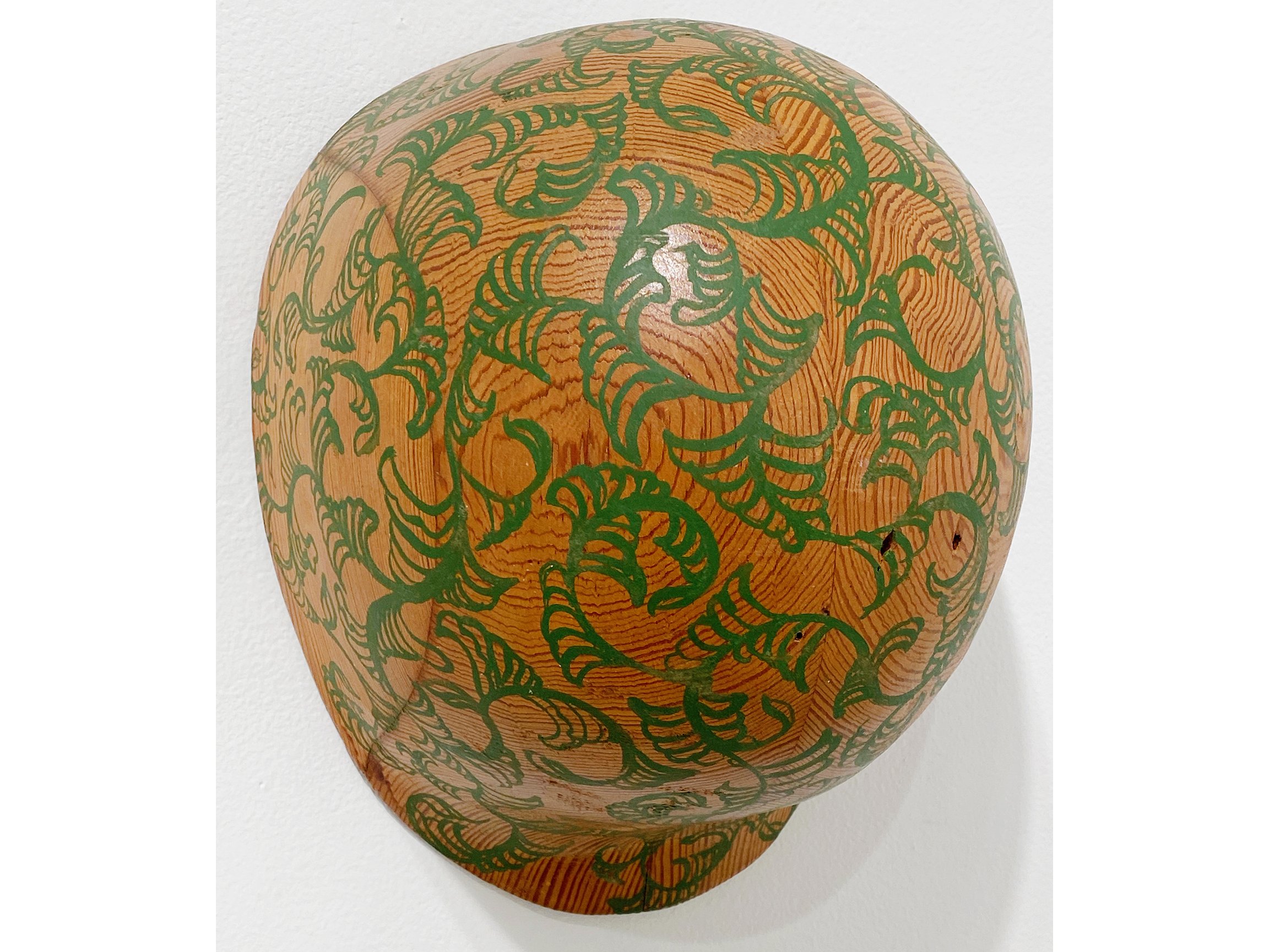

An Pham’s carved wood Helmet is a response to the trauma of the Vietnam War. Pham observed that even when communities were devastated by the war and loss, they rebuilt their homes, their schools and their churches or pagodas, resourcefully using whatever materials were available. Helmet is carved from southern yellow pine, repurposed from beams that the artist found discarded during a renovation of an old house in Brooklyn. The botanical pattern carefully applied to the form is both reminiscent of – and in contrast to – camouflage. It symbolizes regeneration, the way nature eventually reclaims the detritus of war. Pham’s poignant but hopeful piece recalls the statement by Anselm Kiefer, “Ruins, for me, are a beginning.”

Mike Cloud’s mixed-media painting Khan endeavors to bridge the distance between artist, subject and viewer via an act of communal reconciliation. The works in this series push the boundaries of portraiture, asking if it’s possible for painting to speak to the human condition without it becoming shallow gaze or spectacle. These “broken icons” hold space with the entirety of the person, including the emotional extremes of pain and suffering. Jiah Khan was a young, popular Bollywood actor who was found hanging from a ceiling fan in her bedroom of her family's residence in Juhu, Mumbai in 2013. Cloud’s portrait asks viewers to be brave enough to hold all of it and asks how, why and where in society do we resist the urge to flatten a story or an essence, dismantling the complexity which paints a more challenging but truer picture.

Zarina’s woodcut Rani’s Garden is an homage to her sister Rani’s botanical garden, which she maintained at her home in Pakistan. Rani cultivated many plants that she and Zarina knew from their childhood home in India. The image points to the story of a cherished place, in Zarina’s characteristic method of fusing the personal and the foundational, with the repeated leaf-border suggesting the geometries of a garden plot, and the center the portrait of a single flower. Rani’s Garden subtly suggests that the garden is not a neutral place. Its caretakers’ hands – often generations of hands – participate daily in communing with the past. The long story of their family’s years together is carried in the plants, the garden itself a living record.

Yamini Nayar‘s C-print Luck is the Residue of Design is a view into a mysterious room with ancient-looking walls and what appears to be the detritus of human activity. Drawing on Modernist architectural language as well as her Indian ancestry, Nayar creates compelling spaces via richly material surfaces and a shifting sense of scale. She describes her work as “exploring psychological relationships to the built environment, the tensions between planned and informal architectures, memory and erasure, material and psychic spaces.” Nayar’s structures are built in her studio from cardboard, plaster, paint, wood, photos, and other scraps. The resulting construction is then photographed, with only one image of each sculpture ultimately printed. The sculptural models are ephemeral; once completed and photographed, they are subsequently destroyed so the process can be repeated. The photo remains, as a trace of memory, the only record of the 3-dimensional work’s existence.

Amy Yoshitsu's photo-based piece Soap and Sake reminds us that the history of a place is never fully in the past – or, as William Faulkner famously wrote, “The past is never dead. It's not even past." The background image shows the location of the first factory in Berkeley, a soap factory, where Chinese workers rebelled against their working conditions. Today it is a sake factory owned by a Japanese company. Yoshitsu, whose ancestry is both Chinese- and Japanese-American, is interested in the way these cultures have interacted over time in the US. The title Soap and Sake, while referring to the history of the factory, also alludes to the body, and the many bodies that inhabited the factory, producing at one time a cleansing aid and later, a libation consumed into the body. Both are substances that, applied to / consumed by the body, disappear – just as narratives of a community can vanish unless they’re carried on or preserved through retelling.

—Sarah Walko

For press inquiries, please contact Andrea Champlin at info@satchelprojects.com.